From the Forest of Wake to Wake Forest College

By Andrew McNeill Canady

Wake Forest University has its roots in Wake County, North Carolina. The school, known first as Wake Forest Institute, began in 1834 on the former plantation of Calvin Jones. Originally from Massachusetts, Jones was a medical doctor who had made his way to Smithfield, North Carolina, in 1795 and later moved to Raleigh in 1803.[1] Over a decade later, Jones married Temperance Williams Jones, a woman from a wealthy farming and slaveholding family. This union brought Calvin Jones more than 20 slaves and made him a member of the planter ranks of the antebellum South.[2]

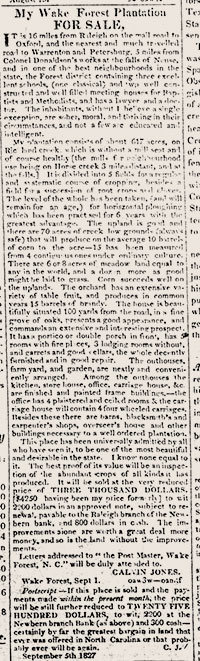

Looking for a place to put his enslaved workers to use, he purchased “Wake Forest,” a property of approximately 615 acres, for $4,000 in 1821 from Davis Battle.[3] In the coming years, this farm produced corn, wheat, cotton, hay, vegetables, fruit, and brandy was distilled. Jones also began to invest in land in western Tennessee with hopes of relocating there.[4] Throughout the 1820s, he tried to sell his “Wake Forest Plantation” on several occasions but with no success.[5] In 1832, the recently established Baptist State Convention of North Carolina was looking for a site for a proposed school, and several representatives of this group purchased Wake Forest for $2,000 from Jones.[6] Soon he and his family relocated to his Tennessee estate, taking along with them approximately 40 enslaved men, women, and children.[7] The plantation he left behind, which included his home, seven slave cabins, and various outbuildings, became the site of the new Baptist school.

During Wake Forest’s period as an Institute (1834–1838), the school operated a farm on the property, requiring the young men and boys who attended to complete several hours of manual labor each day.[8] Wake Forest also ran a steward’s department that provided meals and washing for students and faculty. From the start, the school hired enslaved blacks for agricultural work, cooking, washing and other domestic tasks.

The practice of hiring slaves from slaveowners was common in the South in this period.[9] Hirers paid the slaveowner for the slaves’ time. The contracts, often made for one year, normally required the hirer to pay taxes on the slaves and to provide clothing for them. Wake Forest was not alone in its practice of hiring slaves; other southern schools, including the University of North Carolina, Salem, Hampden-Sydney, William and Mary, the University of Virginia, Furman, and Mercer, did the same.[10]

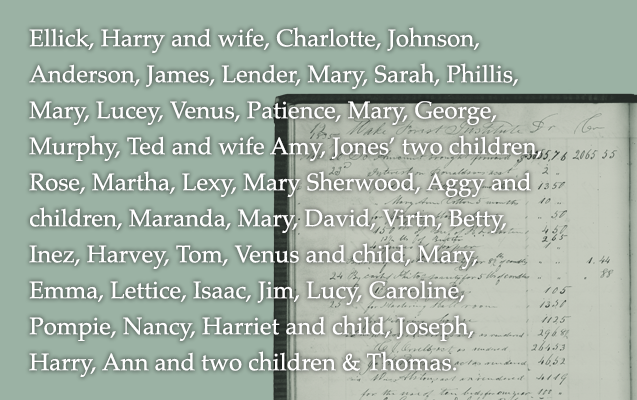

A Wake Forest account book from 1834 shows that four enslaved African Americans were hired that year. The names listed were Ellick; “Harry & wife;” and Charlotte.[11] As student numbers grew, more enslaved blacks were hired in the coming years. Thirteen – Johnson, Anderson, James, Lender, Mary, Sarah, Phillis, Mary, Lucey, Venus, Patience, Mary, and George – were hired in 1835 and approximately 16 were hired in 1836. Records indicate they were known as Murphy; “Ted & wife Amy Jones’ 2 children;” Rose; Martha; Lexy; Mary Sherwood; “Aggy, her children & Maranda;” Mary Harris; David; and Anderson.[12] Account records from Wake Forest for 1837 and 1838 do not exist, but undoubtedly this practice continued in those years as well. During the Institute years, the trustees also employed a white farmer or “overseer.” Three men held this position. One of them was Henry Wall, a previous overseer of Calvin Jones’ Wake Forest plantation.[13]

As the school grew during the period of the Institute, the Board of Trustees decided to erect a “College Building.”[14] In 1835, John Berry, a local architect from Hillsborough, was contracted to build this large, multi-storied brick complex. Berry’s workforce was made up of enslaved laborers, and they moved with him to Wake Forest during the construction process.[15] As the College Building was being completed, two of these enslaved African American men were killed in a fall.[16] They were buried together in a grave on Wake Forest’s property, and a brick wall was built around it. No tombstone with their names, however, was placed there. In the late 1800s, for some unspecified reason, this site was cleared, and its exact location remains unknown at this time.[17]

In 1839, Wake Forest transitioned from Institute to College.[18] Among the powers of the new school was its ability to grant degrees. As the College commenced its operations, it did away with the manual labor requirement and its steward’s department.[19]

The Board of Trustees also began a town. In late 1838, the Trustees had the plantation surveyed, and a plat with streets and lots was created.[20] This property began to be sold the following year. Some of the faculty came to buy land and to build homes there in the coming years. Meals and washing responsibilities soon went into the private hands of the town’s white residents who operated boarding houses. Many of these establishments were run by Wake Forest faculty, including the school’s first president, Samuel Wait, and early professors John Brown White and William Tell Brooks.[21]

All of these men were slaveowners who used their enslaved workers to do the cooking and washing for Wake Forest students. Wake Forest’s farm ran on a limited basis through the early 1840s, and enslaved blacks were again hired to do agricultural work there.[22] The farm, however, went out of operation as more land was sold.

Without it and the steward’s department, Wake Forest College came to hire fewer enslaved blacks than it had during the Institute years. The school, nevertheless, continued to use hired enslaved workers for tasks on its campus, such as sweeping and cleaning the College Building. Account ledgers and board of trustee minutes refer to this person as the “college servant” and numerous enslaved blacks were hired for this role during the remaining antebellum period.[23] One of the men known at this time was Virtn.[24]

Many of the college trustees and financial supporters of the institution were slaveowners, as were all the presidents – Samuel Wait, William Hooper, John Brown White, and Washington Manly Wingate – prior to Emancipation.[25]

In 1835, Wake Forest started a campus church, Wake Forest Baptist. Membership there included students, faculty and their families, local residents, and some of the slaves owned by each of these groups.[26] This congregation remained biracial until the end of the Civil War.[27]

Wake Forest struggled financially for most of the antebellum period. As a result, Wake Forest never owned the slaves that were forced to work on the campus, but it always relied on hired ones. Wake Forest’s leaders’ choice to hire enslaved workers, rather than own them, did not reflect any moral objections to slave ownership. Rather, hiring was less expensive and more flexible to meet their needs in this period. Ownership would have also entailed taking care of elderly slaves too old to work and children born into slavery too young to work. The enslaved laborers Wake Forest hired came from local slaveholders and even from some of the faculty, such as Samuel Wait.[28]

These enslaved workers experienced a difficult position since working at a school brought about complications that other hiring settings did not. Since many Wake Forest students came from slaveholding families, these young men and boys likely found themselves entitled to command these enslaved workers to do their bidding. In effect, the hired slaves at Wake Forest had multiple “masters” with whom to contend.[29] The practice of hiring also separated families during the period of the hiring contract.

Wake Forest received several bequests from North Carolina slaveowners.[30] In the 1840s, Celia Wilder, a woman from Hertford County, dictated that two of her slaves, Betty and Inez, be sold after her death and that the proceeds of this sale ($600) be given to the College.

In 1836, John Blount, a Baptist from Edenton, died and left a major bequest to Wake Forest that included land, homes, and the following slaves: Harvey; Tom; Venus and child; Mary; Emma; and Lettice. His wife, Rebecca Blount, was given lifetime rights, and she remained in possession of this property and these enslaved people until her death in November 1859.

The Wake Forest Board of Trustees checked into this estate numerous times between 1836 and 1859. As soon as Rebecca Blount died, the Trustees dispatched James Simpson Purefoy, board treasurer, Baptist minister, and slaveowner, to take possession of the property and the slaves. Between 1836 and 1859, due to births, the number of slaves had increased to 16 – Isaac; Jim; Lucy; Caroline; Pompie; Emma; Nancy; Harriet and child; Joseph; Harry; Ann and two children; Thomas; and Mary. In the coming months, Harriet and Nancy were hired out for profit. A slave auction was held on May 7, 1860. The sale of these people brought $10,718. One woman, Mary, escaped her enslavement before the sale but was later captured in Norfolk, Virginia and sold there at the end of that month.

From its beginning, Wake Forest College was deeply enmeshed in the southern culture of slavery.

[1] Thomas B. Jones, “Calvin Jones, M.D.: A Case Study in the Practice of Early American Medicine,” North Carolina Historical Review 49 (January 1972), 56; and Jameson Jones, “Calvin Jones: 1775–1846” (2000), folder 107, Calvin Jones Papers #921, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[2] Scholars typically use the term “planter” to denote the ownership of twenty or more slaves.

[3] Davis Battle deed to Calvin Jones, in “Archives—Wills and Gifts” folder, Wake Forest University Financial Services, Winston-Salem, North Carolina; and Marshall DeLancey Haywood, Calvin Jones: Physician, Soldier and Free Mason: 1775–1846 (Bolivar, Tennessee: Press of Oxford Orphanage, 1919), 22.

[4] Jones, “Calvin Jones,” Jones Papers.

[5] See “Also for Sale,” December 5, 1823, Raleigh Register; and “My Wake Forest Plantation FOR SALE,” September 14, 1827, Raleigh Register.

[6] George Washington Paschal, History of Wake Forest College, Volume 1: 1834–1865 (Raleigh: Edward & Broughton Company, 1935), 46. For deed see Purefoy, John and others to Calvin Jones, in “Archives—Wills and Gifts” folder.

[7] Jones, “Calvin Jones,” Jones Papers.

[8] Paschal, History of Wake Forest 1: 65–91 and 449–452.

[9] Jonathan D. Martin, Divided Mastery: Slave Hiring in the American South (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2004).

[10] See Jennifer Oast, Institutional Slavery: Slaveholding Churches, Schools, Colleges, and Businesses in Virginia, 1680–1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 159–202; Seeking Abraham: A Report of Furman University’s Office of the Provost and Task Force on Slavery and Justice (Furman University, 2018), 33–34; B. M. Sanders to Samuel Wait, October 15, 1833, box 4, folder 1, Samuel and Sarah Wait Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Wake Forest University; Grant P. McAllister, “Report for Salem Academy and College: A Study of the School’s Education of Female Slaves and its Involvement with Slavery;” and online exhibition: “The College Servants” in “Slavery and the Making of the University,” https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/slavery/college_servants.

[11] “Enrollment Book,” Wake Forest Historical Museum archives, Wake Forest, North Carolina.

[12] See “Account Book, 1835–1850,” box 1, RG: 25.01, Treasurer’s Office, Special Collections and Archives, Wake Forest University.

[13] Jones, “Calvin Jones,” Jones Papers; promissory note to Henry Wall and receipt, box 8, folder 7, Wait Papers; and E. W. Sikes, “The Genesis of Wake Forest College,” in Literary and Historical Activities in North Carolina: 1900–1905, Vol. I (Raleigh: Publications of the Historical Commission, 1907), 548.

[14] Paschal, History of Wake Forest 1: 104–117.

[15] Henry S. Stroupe, “John Berry—Builder of the First College Building,” The Wake Forest Magazine (February 1965), 13.

[16] Paschal, History of Wake Forest 1: 112.

[17] F. M. Jordan, Life and Labors of Elder F. M. Jordan: For Fifty Years a Preacher of the Gospel Among North Carolina Baptists (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton, 1899), 40.

[18] The Charter and the Laws of the Wake Forest College, Enacted by the Corporation, December, 1838 (Raleigh: Recorder Office, 1839).

[19] Thomas Meredith, Samuel Wait, and Alfred Dockery, “Circular,” January 5, 1839, Biblical Recorder.

[20] Wake Forest Board of Trustee Proceedings, 40, 41, 46, 50, and 51.

[21] Paschal, History of Wake Forest 1: 453–454; and John Brown White to Samuel Wait, December 24, 1841, box 5, folder 5, Wait Papers.

[22] Wake Forest Board of Trustee Proceedings, 49; and “Book A,” Treasurer’s account book, 1839–1852, unprocessed collection, Special Collections and Archives, Wake Forest University.

[23] Wake Forest Board of Trustee Proceedings, 53; and “Book A,” Treasurer’s account book, 1839–1852.

[24] See Ann Eliza Wait to Samuel Wait, March 31, 1839, box 4, folder 8, Wait Papers; and “Book A,” Treasurer’s account book, 1839–1852.

[25] See 1830 and 1840 U.S. Federal Census; and 1850 and 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules.

[26] Minutes and Roll Book, Wake Forest Baptist Church, 1835–1939, North Carolina Baptist Historical Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Wake Forest University.

[27] For more on biracial churches see John B. Boles, ed., Masters & Slaves in the House of the Lord: Race and Religion in the American South, 1740–1870 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1988).

[28] See “Account Book, 1835–1850;” and “Book A,” Treasurer’s account book, 1839–1852.

[29] Oast, Institutional Slavery, 170.

[30] Paschal, History of Wake Forest 1: 213–222.

‘TO STAND WITH AND FOR HUMANITY’

- Foreward

- Beyond Nostalgia: Towards an Inclusive Pro Humanitate

- An Apology

- From the Forest of Wake to Wake Forest College

- Defending the Indefensible: Wake Forest, Baptists and the Bible

- The Waits, Women and Slavery

- Reflections on the Original Wake Forest College Campus and Cemetery

- Examining Our Past, Enriching Our Future: The Slavery, Race and Memory Project at Wake Forest University

- Lest We Forget

- Selected Bibliography and University Archival Resources

- Contributors

Essays from the Wake Forest University Slavery, Race and Memory Project

Edited by Corey D.B. Walker