Defending the Indefensible: Wake Forest, Baptists and the Bible

By Bill J. Leonard

In 1834, the year Wake Forest was founded, a growing majority of white Baptists in the American South assumed chattel slavery to be both socially and biblically justified. Their defense of slavery was not always so solid.

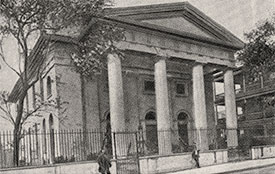

Charleston, SC Built

in 1820

Writing in 1849, looking back on his antislavery sentiments when graduating from the University of North Carolina in 1819, Baptist clergyman Iveson Brookes wrote to a friend: “You perhaps remember what an Antislavery fellow I was at Chapel Hill. I wrote several speeches & compositions against slavery, being about as ignorant on the subject as most of the Northern abolitionists now are.”[1] Brookes published his own work, A Defense of Slavery, in 1850.

Brookes’ early opposition to slavery mirrored the views of some Baptists in the South who acknowledged that slavery was problematic for the region and should ultimately be eliminated, perhaps by sending blacks to Africa through the American Colonization Society. By the 1830s, however, as abolitionist demands for immediate manumission gained momentum in the North, pro-slavery arguments among southern Baptists increased significantly, many with biblical justification.

Richard Furman’s 1822 “biblical defense” of slavery became an important guide for Baptist responses to abolitionism. Furman, pastor of First Baptist Church, Charleston, South Carolina, and namesake of Furman University, declared:

Had the holding of slaves been a moral evil, it cannot be supposed, that the inspired Apostles, who feared not the faces of men, and were ready to lay down their lives in the cause of their God, would have tolerated it, for a moment, in the Christian Church. If they had done so on a principle of accommodation, in cases where the masters remained heathen, to avoid offences and civil commotion; yet, surely, where both master and servant were Christian, as in the case before us, they would have enforced the law of Christ, and required, that the master should liberate his slave in the first instance. But, instead of this, they let the relationship remain untouched, as being lawful and right, and insist on the relative duties. In proving this subject justifiable by Scriptural authority, its morality is also proved; for the Divine Law never sanctions immoral actions.[2]

Furman’s “EXPOSITION” appeared at the end of a year that sent shock waves throughout the South with the discovery of Denmark Vesey’s plans for a slave revolt. Vesey, a freed slave assisted by persons related to Charleston’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, allegedly plotted an armed revolt against slaveholders that would ultimately secure slaves’ freedom in Haiti. The plot was discovered; 131 blacks were arrested; and 35, including Vesey, were hanged. [3] Furman, representing white South Carolina Baptists, implored the state’s governor to declare a “Day of Devotion and Gratitude,” thanking God that the plot was foiled, and the masters saved. He wrote:

But with the knowledge of the conspiracy is united the knowledge of its frustration; and of that, which Devotion and Gratitude should set in a strong light, the merciful interposition of Providence, which produced that frustration.[4]

Furman insisted that slave rebellions were inspired in part by abolitionists’ faulty methods of interpreting scripture. He warned that “certain writers,” many “highly respected,” advocated positions “very unfriendly to the principle and practice of holding slaves,” opinions advanced “directly to disturb the domestic peace” of South Carolina. Their anti-slavery views produced “insubordination and rebellion among the slaves,” particularly their insistence that opposition to slavery was born of “the Holy Scriptures,” and “the genius of Christianity.” By contrast, Furman and the Baptist Convention he represented asserted that anti-slavery was not “just, or well-founded: for the right of holding slaves is clearly established in the Holy Scriptures, both by precept and example.”[5]

Furman and other pro-slavery Baptists made support for slavery essential to biblical orthodoxy, implying that if the Bible was wrong in sanctioning slavery, it might be untrustworthy on the nature of salvation itself. Their literal method of interpreting the Bible aided Baptists in claiming biblical authority to support the institution of chattel slavery. Richard Furman was not the only slaveholding minister to be associated with a Baptist-oriented 19th-century college. Others included Samuel Wait of Wake Forest, William Tryon of Baylor, and the four founding faculty members of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, the Southern Baptist Convention’s first theological school, which originated on the Furman campus in 1859.

Slavery had its cruelties, Furman admitted, noting,

That Christian nations have not done all they might, or should have done, on a principle of Christian benevolence, for the civilization and conversion of the Africans: that much cruelty has been practised in the slave trade, as the benevolent Wilberforce, and others have shown; that much tyranny has been exercised by individuals, as masters over their slaves, and that the religious interests of the latter have been too much neglected by many cannot, will not be denied. But the fullest proof of these facts, will not also prove, that holding men in subjection, as slaves, is a moral evil, and inconsistent with Christianity.[6]

The Bible set forth a “Christian” treatment of slaves, practices often undermined by slave owners. That fact, however, did not negate the scriptural and moral validity of slavery as viable social practice. Furman concluded, “In proving this subject justifiable by Scriptural authority, its morality is also proved; for the Divine Law never sanctions immoral actions.”[7] For Furman, Christian opposition to slavery reflected a “perversion” of scripture, undermined proper Christian instruction for civilizing of slaves, and exacerbated their desire to revolt.

Richard Furman’s “EXPOSITION” was among the earliest of what became a broad collection of antebellum “Bible defenses of slavery,” works that conjured up marks on Cain and curses on Ham as evidence from Genesis that the darker races were deemed inferior by divine act, a biblical foundation for white supremacy. Abolitionist opposition to this biblical hermeneutic set the scene for a Baptist schism.

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) began in Augusta, Georgia, in 1845 after the nationally organized Baptist missionary society (Triennial Convention) rejected appointment of known slaveholder James Reeve as a missionary. Reeve’s name was put forward by Georgia Baptists as a test case. When it was rejected, the SBC was founded “for eliciting, combining, and directing the energies of the whole denomination in one sacred effort, for the propagation of the gospel.” The original charter made no mention of the real reason for SBC origins: support for chattel slavery.[8]

The Baptist Convention of North Carolina did not act as hastily as Baptists in Virginia and the Deep South in calling for a new denomination. When reconciliation with the Triennial Convention seemed impossible, North Carolinians voted to give the SBC their “cordial” affirmation and unite with it. Nonetheless, controversy over slavery continued.

An 1852 publication titled Domestic Slavery Considered as a Scriptural Institution contained extensive correspondence on slavery between South Carolina pastor Richard Fuller and Brown University President Francis Wayland. Fuller reasserted Richard Furman’s arguments, contending that “both testaments constitute one entire canon, and that they furnish a complete rule of faith and practice.” He concluded: “WHAT GOD SANCTIONED IN THE OLD TESTAMENT, AND PERMITTED IN THE NEW, CANNOT BE A SIN.”[9]

Francis Wayland was no abolitionist; rather he supported gradual emancipation, fearing that slaves were not yet ready for freedom. He opposed the militancy of the abolitionists but supported their contention that Jesus’ Golden Rule negated slavery as a viable practice, especially for Christians.”[10]

Wayland’s later opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska compromise bill on slavery (1854) elicited angry responses from North Carolina Baptists. The state’s Baptist Biblical Recorder declared that Wayland had “misrepresented” the views of Southerners by suggesting that they acknowledged slavery to be “wrong, utterly indefensible in itself and the great curse that rests upon the Southern States.” Those remarks, along with his opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska bill, pushed Wake Forest trustees to rule that “Wayland’s Moral Science, be dispensed with, in the Instruction given at Wake Forest College.”[11] Moral Science apparently had limited impact on the campus, since, as George Paschal wrote in his history of Wake Forest:

The labor of making brick and of building was done by the Slaves of Captain Berry, two of whom lost their lives by a fall from the building. They were buried in the Wake Forest cemetery both in one pit grave with walls of brick extending two feet above ground.[12]

The legacy of slavery was set, for school and denomination alike.

[1] Larry E. Tise, Proslavery: A History of the Defense of Slavery In America, 1701-1840 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1987), 302.

[2] Richard Furman, “EXPOSITION of the Views of the Baptists, Relative to the Coloured Population in the United States in a Communication to the Governor of South-Carolina,” in Bill J. Leonard, Early American Christianity (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1983), 382-383.

[3][3] H. Shelton Smith, In His Image, But . . . Racism in Southern Religion, 1780-1910 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1972), 54.

[4] Furman, “EXPOSITION,” 379.

[5] Ibid, 381.

[6] Ibid, 385.

[7] Ibid, 383.

[8] “The Original Constitution of the Southern Baptist Convention, http://baptiststudiesonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/02/constitution-of-the-sbc.pdf.

[9] Domestic Slavery Considered as a Scriptural Institution: In a Correspondence Between the Rev. Richard Fuller, of Beaufort, S.C., and the Rev. Francis Wayland, of Providence, R.I., (New York, 1845), 170. Capital letters used in the original text.

[10] Douglas Weaver, “Review: Domestic Slavery Considered As a Scriptural Institution,” Journal of Southern Religion 15 (2013): http://jsr.fsu.edu/issues/vol15/weaver.html.

[11] Willie Grier Todd, “North Carolina Baptists and Slavery, North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. 24, No. 2 (April 1947), 153, citing Minutes Board of Trustees, Wake Forest College, Tuesday, June 10, 1856.

[12] George W. Paschal, History of Wake Forest College (Wake Forest, NC: Wake Forest College, 1935), I (1834-2865),112.

‘TO STAND WITH AND FOR HUMANITY’

- Foreward

- Beyond Nostalgia: Towards an Inclusive Pro Humanitate

- An Apology

- From the Forest of Wake to Wake Forest College

- Defending the Indefensible: Wake Forest, Baptists and the Bible

- The Waits, Women and Slavery

- Reflections on the Original Wake Forest College Campus and Cemetery

- Examining Our Past, Enriching Our Future: The Slavery, Race and Memory Project at Wake Forest University

- Lest We Forget

- Selected Bibliography and University Archival Resources

- Contributors

Essays from the Wake Forest University Slavery, Race and Memory Project

Edited by Corey D.B. Walker